In my last post, I used the philosophical problem of the Sorites Paradox to illustrate the difficulty in pinning down exactly what counts as a “real” book of the Bible. A recent essay by Ronald Hendel, Professor of Hebrew Bible and Jewish Studies at UC Berkeley, might help to clarify our thoughts enough to offer a tentative answer.[1] In “What Is a Biblical Book?” Hendel uses the philosophy of art to propose an answer to the question we looked at in my last post. [Spoiler Alert: This post will be a little more technical than my last one.]

In my last post, I used the philosophical problem of the Sorites Paradox to illustrate the difficulty in pinning down exactly what counts as a “real” book of the Bible. A recent essay by Ronald Hendel, Professor of Hebrew Bible and Jewish Studies at UC Berkeley, might help to clarify our thoughts enough to offer a tentative answer.[1] In “What Is a Biblical Book?” Hendel uses the philosophy of art to propose an answer to the question we looked at in my last post. [Spoiler Alert: This post will be a little more technical than my last one.]

In The Metaphysics of Morals, Immanuel Kant posed the philosophical question, “What is a book?” Hendel uses this question as a baseline to begin thinking about biblical books. According to Hendel’s reading of Kant, a book is a “physical object—that is, a manuscript or printed text” that functions semiotically “‘to represent a discourse’ to the public…by means of ‘visible linguistic signs.’”[2] In other words, we recognize the Gospel of Luke as the Gospel of Luke by means of linguistic and semiotic markers that are generally recognizable to those who have read the Gospel of Luke before. When we read an ancient text about the birth of Jesus that features shepherds and angels singing “Glory to God in the highest,” we can be reasonably certain we are reading the Gospel of Luke.

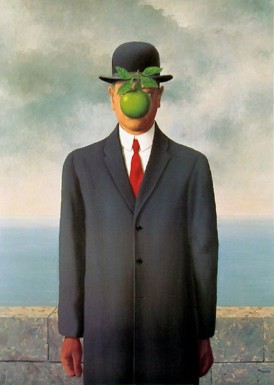

Next, Hendel next builds on Nelson Goodman’s distinction between autographic and allographic arts and Charles Peirce and Richard Wollheim’s distinction between types and tokens to narrow and sharpen the way we think about biblical books. While an autographic work, according to Goodman, is a “single object, locatable in space and time,” like a “painting or a sculpture” (e.g. da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or Rodin’s The Kiss), an allographic work “exist[s] in multiple and dispersed copies, and any accurate copy is an authentic instantiation of the artwork.”[3] An autographic work cannot be authentically duplicated—copies, even extremely convincing copies, are referred to either as “forgeries” or “prints.” The poster of René Magritte’s The Son of Man that hung on my dorm room wall in college was not the work of Magritte’s own hand, but a cheap reproduction purchased from the campus bookstore. By contrast, an allographic work does not depend upon a pristine, Platonic “original,” but is instead marked by the fact that any copy of the work is a genuine instantiation of that work. The PDF of Hendel’s essay that I read, for instance, is not the same instantiation as the hard copy of Hendel’s essay found in the Library of Congress, yet both copies are unquestionably understood to be the same essay.

Curiously, however, Goodman’s conception of an allographic work depends upon very strict limitations with regard to variations among texts. Should a copy vary from the author’s manuscript by a single character, according to Goodman, such a variation would constitute an entirely different work.[4] It is not difficult to see how Goodman’s hypothesis falls short of proper application to the field of New Testament textual criticism. Not only are the original manuscripts of the Gospel texts unavailable to us (assuming we would even recognize them if they existed), but should we apply Goodman’s hypothesis unaltered to ancient manuscripts of the Gospel of Luke, for example, we would find that the Gospel of Luke does not exist; we would have merely a number of texts with remarkable linguistic/semiotic similarities. To remedy Goodman’s oversight, Hendel points out that texts like James Joyce’s Ulysses and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass exist in a legion of variations and editions, yet all of these variations are still considered instantiations of the same works.

Instead, Hendel suggests that Goodman’s hypothesis be revised to include “sameness of words and word sequences,” or “sameness of substantive readings.”[5] In other words, if two compositions contain extended passages of identical or closely parallel text, chances are good that they are both instantiations of the same allographic work. In this way, Hendel maintains that books are doubly allographic: they are allographic in the sense that any number of copies of an original work constitute instantiations of that same work, but they are also allographic in the sense that variations may exist even among those copies and yet still be considered instantiations of the same work.[6] Thus, each of those twelve early copies of the Gospel of Luke mentioned above can still be considered the Gospel of Luke, despite their numerous textual variants. Yet this still leaves the question posed by the Sorites Paradox in my last post: at what point does a text vary so much that it is no longer recognizable as a particular allographic instantiation? Or, as Hendel puts it, “Can we specify a limit to the range of allowable variation?”[7]

To answer this question, Hendel employs the distinction between type and token as a critical method of distinguishing between copies of texts. A type, according to Hendel’s reading of Peirce and Wollheim, is an abstract concept that reflects a sort of Platonic ideal of a given object, word, or idea. On the other hand, a token is a particular instantiation of a type.[8] For example, the specific bike that I ride to the university almost every day—an 8-speed 2015 Kona Dew—is a particular instantiation of the same model produced by Kona. My particular bike is a token, while Kona’s model design is a type. Even more generally, it could be said that my bike is a token of the concept of bicycle, which is also a type. Likewise, according to Hendel’s argument, we could also say that the idea of the Gospel of Luke is a type, while the individual copies and manuscript fragments mentioned above are tokens of the Third Gospel. Thus the answer to the question posed by the Sorites Paradox to discipline of textual criticism, according to Hendel, is something like this: As long as the linguistic and semiotic markers of a token text bear close enough resemblance to what readers recognize as the allographic type of that text, that particular token text is acknowledged as a genuine instantiation of the allographic type text.

What do you think? Is Hendel’s answer reasonable?

_______________________

[1] Ronald Hendel, “What Is a Biblical Book?” in From Author to Copyist: Essays on the Composition, Redaction, and Transmission of the Hebrew Bible, ed. by Cana Werman (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2015), 283-302.

[2] Ibid, 284.

[3] Ibid, 285.

[4] Ibid, 286.

[5] Ibid, 287.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, 289.

Thanks for the interesting follow-up article.

In response to your closing question:

“As long as the linguistic and semiotic markers of a token text bear close enough resemblance to what readers recognize as the allographic type of that text, that particular token text is acknowledged as a genuine instantiation of the allographic type text.

What do you think? Is Hendel’s answer reasonable?”

I suppose the next question this immediately raises is this: where is the boundary between “close enough resemblance” and “not close enough resemblance” that determines whether a particular text is a token of a given type? Can it be objectively defined or is it entirely subjective? Is it simply a matter of scholarly consensus?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for commenting, Rob. I have another post coming on Monday that might address your question a little better, but for now I’ll just say that I don’t think scholarly consensus has anything to do with it, and I think it is entirely subjective—although not on an individual basis. When you look at the way the early church understood canon, it was not a mysterious, cloak-and-dagger affair as made popular in our cultural imagination by folks like Dan Brown. What’s interesting is that broad consensus slowly emerged over the first four centuries as to what books were the most useful for religious instruction. More to your question, though: in my next post I offer around 8 or 10 different modern examples of how biblical texts and canon are kind of flexible even today. The buzzard thing about the Christian tradition is that this flexibility is not present in either Judaism or Islam, which is an oddity that I’ll have to think and write about more in the future.

LikeLike

Thanks for your reply, Joshua. I look forward to your next post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, I meant to say “bizarre,” not “buzzard.”

LikeLike

Yeah, I noticed that, but I kinda liked the buzzard so I let it pass 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think this is quite true: “The [bizarre] thing about the Christian tradition is that this flexibility is not present in either Judaism or Islam.” Definitely not in Islam, but Judaism had a rather flexible practice regarding translations, not just because of the Septuagint and variations in that, but because there were variations in the Hebrew texts as well. At least that is my impression of what I’ve heard was evident during the 2nd Temple era.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment, rwwilson147. Let me clarify my statement a bit (without going into too much detail, since you’ve touched on some ideas that will be the focus of my final post on canon and authority, which will be posted this evening).

Yes, you are absolutely correct that the Septuagint is an example of textual innovation in the Judaic tradition. However, the Septuagint only saw heavy use among Jews for about four centuries. Aside from the Septuagint, Jews universally use the Masoretic text (you won’t find the Septuagint read in Jewish synagogues today). Judaism is *extremely* particular about the actual words on the page, right down to how the Book is even produced. It is treated as if it were a person; a major difference between early Jewish and Christian theology is that while the Jews had a theology of the Logos, the Logos was actually the Torah as opposed to the incarnational Logos of Christianity. The Masoretes took great pains not to disturb the “original text” of the Hebrew Bible (scare quotes added because that’s a conversation for another time) in their vowel pointing system, even to the extent where if a grammatical or spelling mistake was discovered, rather than correct the mistake itself they would point it in such a way as to compensate for the mistake. Today in synagogues and mosques around the world, the only definitive editions of the holy books of Judaism and Islam are those which are copied and read aloud in their original languages (unlike Christianity, which promotes a plurality of translations, and how many Christian churches do you know that read the New Testament aloud in Greek? Aside from churches in Greece, of course).

In short, while Judaism and Islam are both “Religions of the Book” that place a huge emphasis on the particular way the text is created, they both have a pretty expansive interpretive tradition. By contrast, however, Christianity historically has had few qualms about blatantly adjusting the text itself (see my previous post, which mentions the insertion of the Pericope Adulterae into the Gospel of Luke) while simultaneously holding to a relatively restrictive interpretive tradition (e.g. orthodoxy). You won’t find any thing like “Biblezines” or “The Message” in Judaism or Islam.

LikeLike

Seems a bit like an apples and oranges kind of comparison: medieval Jewish and Islamic practices versus earlier, centuries following C.E. treatment of Christian texts and subsequent interpretational codification. Overall I don’t think the antithesis stands. Christianity today is certainly not devoid of an “expansive interpretive tradition,” quite the contrary. But interpretive traditions are also different from modes of dealing with textual variations. Each tradition has rather different ways of dealing with their particular texts, and different ways at different historical periods in relation to their textual origins, and thence also different interpretive practices. The history of texts and the history of interpretive traditions seem more suited to be sussed out separately.

LikeLike

rwwilson174, you’re right about Christianity having an expansive interpretive tradition—the umbrella of Christianity, even of Christian orthodoxy, is very wide (although again, there are limits: hence the development of the idea of “orthodoxy” in the first place). And while your point about medieval textual practices in Judaism and Islam is well taken (e.g. the Masoretes), these textual practices reach back centuries earlier in origin. The rise of the Haggadot, Halakhot, and Talmudic and Mishnaic traditions in the first centuries following the destruction of the Temple (i.e. concurrent with the development of the Christian textual tradition) attests to the fact that Jews were hesitant to make even the slightest change to their holy text, whereas (presumably Gentile) Christian scribes tinkered with the text all the time, as thousands of textual variants in the New Testament will attest. This is the point I’ve been trying to make all along. Textual variants, in both the Judaic and Islamic traditions, are *exceedingly* few, and (in the Judaic tradition, at least) are carefully preserved as *part* of the text, whereas in the Christian tradition scribes would simply change the text to suit their needs.

LikeLike

I think that this problem is an interesting parallel to the problem of biological classification. How different must two individuals be in order to be members of different species? How different must species be to represent different genera? The questions are answered with varying degrees of subjectivity in biology as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re absolutely right, Allen. As a matter of fact, one thing that I meant to mention in this post (or at least one of my three posts about canon) is the fact that I’m curious about what basically boils down to taxonomy.

LikeLike

Also, this.

http://assets.amuniversal.com/b1038de0b98e013340c2005056a9545d

LikeLiked by 1 person